What was MotoGP like 50 years ago?

They say history is another country, and MotoGP in the early 1970s was so different to its modern-day counterpart to be barely recognisable.

A new book – Continental Circus 2 – by Dutch photographers Jan and Hetty Burgers portrays the world of motorcycle grand prix racing in the early 1970s, when the racing was dangerous and the paddock was a wild place to live and work, more like a circus camp than a business park.

The Burgers lived with the riders, pitching their tent among the rusting vans and tatty caravans as the so-called Continental Circus worked its way around Europe. Conditions were as primitive as the racing was deadly, but people can come together when times are hard and at that time the paddock was largely a brotherhood of racing fanatics, who would undergo any hardship, so long as they got their kicks on Sunday afternoons.

What makes the Burgers’ work so remarkable is the fact that they didn’t just focus on close-cropped photos of riders going around corners; they went wider, bringing in the surroundings, so you get a real feel for what the racing life was all about. The book is a must for anyone who appreciates the history of motorcycle racing.

Yes, it’s motorcycle racing but it could hardly be more different to MotoGP in 2022: two-strokes, push starts, no starting lights, plus mechanics, photographers and hangers-on stood right at the edge of the track.

The picture at the top shows the start of the 350cc Italian grand prix at Imola, May 1974, with bodies cocked for the big push and all eyes on an official, just out of shot, who’s about to drop the Italian flag to signal the start of the race.

Finn Tepi Länsivuori No.2 starts from pole, next to factory Yamaha team-mate Giacomo Agostini, who had recently defected from MV Agusta, then Frenchmen Michel Rougerie and Patrick Pons and Spaniard Victor Palomo.

Ago won the race on his way to that year’s 350cc title, which he had won with MV four-strokes from 1968 to 1973. Note the Marlboro sticker on his helmet – the Italian stallion was the first GP rider to get backing from the tobacco industry.

They all ride Yamaha TZ350cc twins, except Rougerie, aboard a Harley-Davidson, which earlier that year had bought Italian marque Aermacchi and rebadged Aermacchi’s GP bikes.

During this era the 350cc and 250cc classes were the backbone of grand prix racing, largely because privateers had a better chance of making ends meet by contesting two categories with near-identical machines: a TZ250 and a TZ350.

Pons won the Formula 750 world championship in 1979 and was killed during the British 500cc GP at Silverstone in 1980, when he fell and was run over by Rougerie, who lost his life nine months later when he crashed during the Yugoslavian 350cc GP at Rijeka and was also hit by a following machine.

Palomo won the 1976 F750 title – Spain’s first bike-bike world champion – and died in 1985, due to complications from injuries suffered during the 1979 24 Hours of Montjuic race.

Chas Mortimer was the epitome of a 1970s grand prix privateer (although at times he had support from the Yamaha factory). He raced everything everywhere and became the only rider to win 125cc, 250cc, 350cc and 500cc GPs and a Formula 750 world championship race. This unique achievement, in my opinion, makes him worthy of MotoGP legend status.

His father Charles was a star at Brooklands during the 1920s and 1930s. Dad also started Britain’s first motorcycle racing school, at Brands Hatch, which he gave to Chas, who promptly sold it, so he could afford to become a professional motorcycle racer.

In 1972 Mortimer scored Yamaha’s first premier-class victory when he won the 500cc GP at Montjuic, riding an over-bored TR3, the air-cooled precursor of the water-cooled TZ350. The minimum engine capacity to compete in 500 races was 351cc. Mortimer’s engine measured 354cc, or at least it did until he seized a piston in practice, damaging that 354cc cylinder. He didn’t have a spare over-bored cylinder, so he fitted a 347cc cylinder.

Many riders at that time didn’t even bother to fit bigger cylinders to their 350s to make them eligible for 500 races, merely swapping blue plates for yellow. So was Mortimer’s winning engine legal or not?

“As I got on the rostrum, Dave Simmonds [who had finished second on his Kawasaki H1R 500cc triple] asked me if my bike really was a 354,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t know’, but I think it would have been just over 350.”

Indeed it would’ve measured 350.5cc, so above 350cc but not above 351cc.

Jarno Saarinen started out ice racing and rapidly climbed to the top of road-racing, thanks to his huge riding talent technical skills; he was an engineer by trade. It was Saarinen who inspired ‘King’ Kenny Roberts to use the hang-off riding style that soon had riders dragging their knees on the asphalt.

Roberts recalls: “I started hanging off at Ontario Motor Speedway at the end of 1972. It had this right-hand horseshoe where I felt so uncomfortable, like I was going to crash. Saarinen came over to race that year and I watched him – he leaned off the side of the bike with his knee out, so I leaned off in that horseshoe and all of a sudden I didn’t have that bad feeling”.

Saarinen is still rated one of the best motorcycle racers of all time, even though his star shone so briefly. He was leading the 1973 250 and 500cc world championships when he was killed during the 1973 Italian 250cc Grand Prix at Monza.

Saarinen lost his life in a horrific first-lap pile-up, caused by Renzo Pasolini’s Harley-Davidson seizing a piston as the pack hurtled into the daunting, guardrail-lined 140mph Curve Grande. Fourteen riders crashed, several badly injured, with Saarinen and Pasolini dead. The race wasn’t stopped. The survivors continued racing, threading their way through the Curve Grande carnage of broken bodies, bikes and blazing haybales, until they gave up of their own accord.

Two months later bikes raced again at Monza. Before this national meeting, Dr Claudio Costa – the founder of MotoGP’s Clinica Mobile – asked the promoters to place an ambulance at Curve Grande but his request was refused. Once again there was a pile-up at the corner. It took 20 minutes for an ambulance to get to the scene – too late for the three riders who perished.

The relentless rise of the two-stroke had convinced Agostini that he would have to join the revolution; it was just a case of when. Yamaha had been wooing him for a while until he finally signed in December 1973.

“In 1971 I thought it was too early to race a two-stroke – they were always seizing engines,” he recalls. “But by 1973 I could see that all the two-strokes were getting faster and safer, while it was very difficult to find more horsepower with the four-stroke, so it was time to change.”

And yet Ago’s first season with Yamaha’s 0W20 500 four and TZ350 twin wasn’t easy – the bikes had tiny powerbands, vibrated, seized and drank fuel. The 1974 0W20 did 11 miles to the gallon, which is why he ran out of fuel at Monza. (Modern MotoGP bikes do around 17 miles per gallon.) MV retained its 500 crown in 1974, with Phil Read, but by 1975 the Yamaha was much, much better, allowing Ago to win the two-stroke’s first 500cc championship.

Monza 1974 was the seminal Suzuki RG500’s third grand prix. Sheene had ridden the rotary-valve square-four to second place in its debut GP a few weeks earlier at Clermont-Ferrand, France. He crashed out at Monza, while chasing Ago, allowing MV’s Gianfranco Bonera to win the race.

Sheene won the RG’s first GP at Assen in 1975 and the bike dominated the premier-class from 1976, when Suzuki sold production versions to privateers. The following season all but five of the 35 riders that scored 500cc GP points rode RG500s.

Johnny Cecotto was a 19-year-old rookie from Venezuela, who went on to win that year’s 350 world title, becoming the sport’s youngest world champion. Villa won a 250 title hat-trick in 1974, 1975 and 1976. He also won the 350 crown in 1976.

The paddock wasn’t all gold and glitter in the 1970s, instead populated by ratty vans, caravans, tents and awnings. This is the paddock residence of Swiss sidecar racers Rudi Kurth and Dane Rowe – their modified Citroen estate transported their sidecar and became their hotel room at night. Note the curtains still drawn.

These leathers and washing belong to eight-times GP winner Tepi Länsivuori and his wife Helena. The Finn was a factory Yamaha rider in 1974, when he finished third in the 500cc world championship behind the MV Agustas of Phil Read and Gianfranco Bonera and ahead of team-mate Giacomo Agostini.

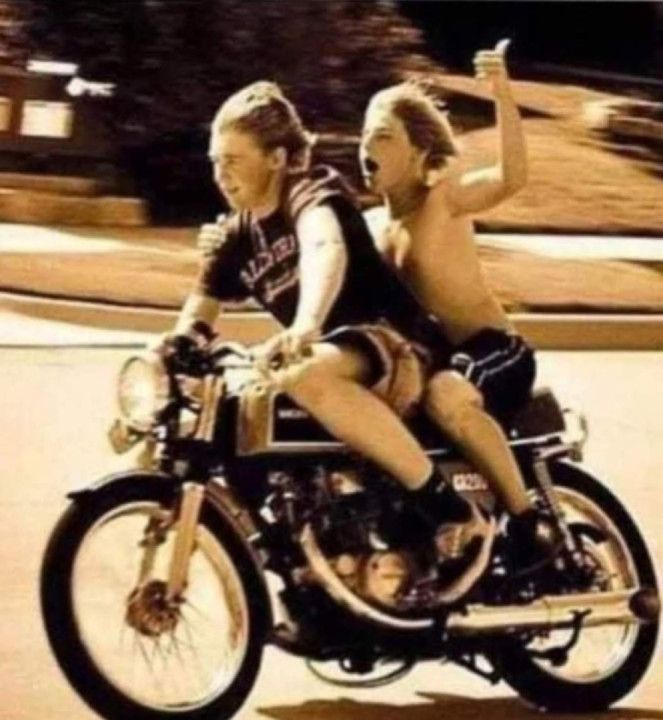

Riders and teams aren’t allowed to hang out washing in the MotoGP paddock these days. The clothing has changed too. When the weather was hot in the 1970s it was entirely normal for riders to wander around the paddock in so-called budgie-smuggler swimwear, while wives and girlfriends wore bikinis.

Imatra was most famous for its railway crossing, which had riders accelerating out of a corner and over railway lines, rendered out of service for the Finnish GP weekend. When ‘King’ Kenny Roberts first raced there in July 1978 he dropped out of the 500cc GP due to ignition failure. Asked if he was angry with Yamaha for the DNF, Roberts replied in typical style: he wasn’t upset, because the problem wasn’t that there was anything wrong with Yamaha ignition systems, the problem was that Yamaha didn’t have a railway crossing at its test track.

Imatra was dropped from the world championships after sidecar driver Jock Taylor was killed there in 1982.

Author: Mat Oxley, Credit: Motorsport Magazine

#MotoGP #Race #Moto #Bike