Dispatch riders had doubly dangerous duties during the Second World War

One shell fell behind him, and when a second exploded just ahead, dispatch rider Gordon Edward Allen knew German gunners were homing in on him.

“They can hear that stupid bike of yours,” said the sergeant giving Allen directions that would take him behind enemy lines. “I’m getting the hell out of here.”

But Allen could not. He had orders to find a medical team stranded behind enemy lines in an area of France about to be bombarded by the Allies.

Allen found the team along a farm lane between Caen and Falaise, burying two of their members. He told them the Germans knew he was nearby, so they needed to exit quietly. “Don’t rev it, because if you do, we’re going to get it,” he told the ambulance driver. “Go down the highway at least two or threemiles before we rev and get the hell out of here.”

Just after they pulled up behind their own lines alongside Allied guns, the shelling started. “The sound was just terrific,” Allen recalled in a Memory Project video. “My bike was blown over from the concussion and the ambulances were bouncing around like peas on a hot griddle. All hell broke loose.”

But the medical unit was saved, thanks to Allen, one of the thousands of daring dispatch riders who served during the Second World War.

There is no single description of the duties of dispatch riders—or DRs, Don Rs, or in Britain, despatch riders—because the term came to be applied to anyone who regularly carried out their job on a motorcycle. The main duty was to deliver messages that could not be trusted to unreliable or insecure telephone or wireless transmissions. This made them instant targets for an enemy eager to ideally capture, or if necessary, destroy the message. To the enemy, shooting the messenger was not a bad idea, either.

Dispatch riders could be part of, or attached to, any unit, but the greatest concentrations were in the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals (RCCS) and the Provost Corps, which provided military police (MP).

DRs delivered messages—everything from battle orders, situational updates, maps or intelligence reports—from headquarters to officers or units that could be located hours of hard driving away, including on—or even past—the front line. They delivered medical supplies and urgently needed parts and equipment, quickly transported personnel where they were needed, and rushed to downed aircraft to rescue surviving Allied aircrew.

They escorted supply convoys, leading them over unmarked routes, darting in and out of the line to keep trucks and tanks at efficient distances apart, fetching stragglers. It was dangerous work. Trying to dodge a tank in a convoy, John Charlwood of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps hit a rut and fell in front of the tank.

“Fortunately, the tank driver, he saw it and he just turned off one track. They told me, ‘You get back on your motorcycle right away because if you stand around and look at it for very long, you won’t.’ So, that’s what I did.”

Civilian vehicles would break into a convoy queue, “then would try to skip along to get ahead, and a DR would be coming along hell-bent for leather and he’d bang right into him, and that was the end of his game. There was a lot killed like that,” Donald Gorman, who was wounded and taken prisoner at Dieppe in August 1942, said in a Memory Project interview.

And DRs could be just victims of circumstance. Chick Owens, who ended the war with the RCCS, narrowly escaped death from a V-2 bomb in Antwerp, Belgium. His blue-and-white armband giving him priority, he was waved through an intersection by three MPs directing traffic.

“Less than 30 seconds [later], this ungodly explosion went off, and then this piece of metal about four feet long landed about six feet from me…. So I turned back and all I could see of the three MPs was one armband…[they] were all blown to pieces. There were probably 300, 400 casualties. [in a café] I could see these people looking out, but they were just looking straight ahead; they were killed by concussion.”

Ewart Tucker, a DR who witnessed the destruction of Cassino, Italy, had been asked to lead a jeep carrying a medic and a padre “into where the boys were under extreme fire. My bike was literally shot out from under me. Gas tank was punctured, the tires were punctured, the fenders and everything. Every day was a close call, let’s put it that way.”

Sometimes it seemed as if nothing could keep a tenacious DR from completing his duty. They “displayed remarkable skill in traversing the gaps at the blown bridges with their motorcycles, sometimes lowering them with ropes at difficult diversions,” to deliver rations to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, which had laboriously traversed the obstacle course of land deliberately ravaged by German troops in their retreat from Delianuova, Italy, in 1943. DRs also “explored far out on either flank, rapidly building up the divisional intelligence picture,” according to the Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Volume II.

The Intelligence Corps also made extensive use of motorcycles to get them into battle-torn areas close behind the infantry, note Ken Messenger and Max Burns in The Winged Wheel Patch, A History of the Canadian Military Motorcycle and Rider (WWP). Signal corps DRs wore a patch on the left arm, below the elbow, of a wheel with wings under the initials DR.

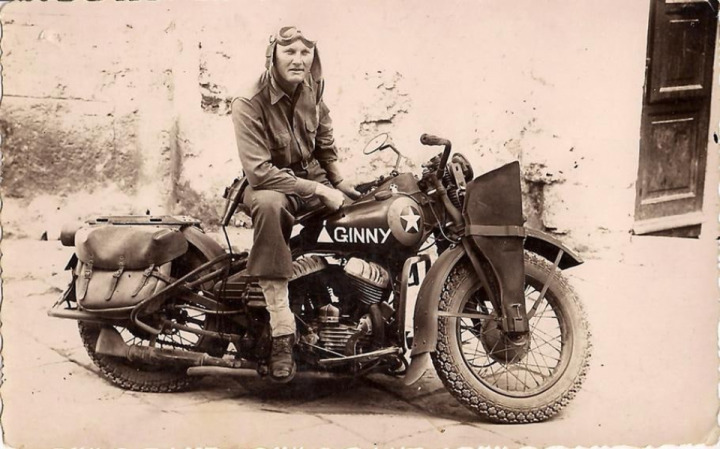

Uniforms varied depending on service, but basics included high boots, leather vests, canvas trousers, weatherproof jackets, helmets, goggles and gloves with wide cuffs. Some wore wide kidney belts to limit injury from juddering over rough terrain.

What DRs did not have was a good means of self-defence. They were issued revolvers in England, which were replaced by Sten guns or Thompson machine guns in Europe. But, notes WWP, “the Sten gun had a reputation for discharging occasionally when the motorcycle hit a bump, and a rider under fire usually couldn’t afford the time to stop and set up the Thomson.” DRs had to rely on speed and agility. The machine gun, the book wryly notes, was good for opening wine barrels.

But the thing that set Canadian DRs apart, the thing that earned them the title Crazy Canucks, was their habit of riding on the gas tank—risking discipline in doing so.

“Sitting right up forward on the tank in their usual way, they just bulldozed their way through, ignoring ruts and water holes,” said one British DR quoted in WWP. “We had never seen anything like it.”

About 700,000 motorcycles were produced for the Allies. Harley-Davidsons used in England were swapped for lighter bikes after D-Day. “If you went into a bomb crater, you couldn’t lift the Harley out, but the smaller machine, you could pick it up and get out all by yourself,” Alex Alton of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada recalled.

Although Norton and Harley-Davidson motorcycles were the customary ride, Canadians serving in theatres around the world also used Triumphs, Enfields, BSAs, Indians, Clynos, Ariels, Welbikes, and even the odd captured BMW.

It’s unlikely any DR ended the war riding the same bike he started out on. “I smashed up nine motorcycles altogether in Italy,” said Trooper Darrell White.

The Germans dismissed Canadian combat prowess with propagandist Lord Haw Haw’s oft-quoted jeer: “Just give them a bottle of whisky and a motorcycle and they will kill themselves.”

DRs had one of the most dangerous jobs—even before they engaged in battle. “There was a heavy toll [even while training]… particularly dispatch riders,” says the Official History of the Canadian Medical Service, 1939-1945.

On a narrow stone-fenced road, “I…came around a corner at about 60 miles per hour and there was a British truck passing another,” rider Lou Lapointe of the Royal Canadian Engineers recalled in WWP.

In November 1941, just after Lapointe awoke in hospital with a fractured skull, the British government made helmets mandatory for military motorcyclists. But the helmets were widely loathed and sometimes doffed when out of sight of the brass. Goggles were also unpopular, in fine or foul weather. In clear weather, sun glinting off the lenses alerted snipers, while DRs were blinded by muck-covered goggles in foul weather.

Neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns recorded 2,279 riders’ deaths in the first 21 months of the war, up more than 20 per cent from the same period pre-war. He also charted a reduction in fatalities and severity of injuries after wearing helmets became mandatory. By 1943, British army motorcycle fatalities fell from 200 to 50 a month. Even so, hundreds of DRs were killed by enemy or accident each year.

“A rider had to become proficient in laying the bike down and sliding under the truck,” recalled Private Jack Aisbitt of the 3rd Canadian Anti-Tank Regiment.

“I came around a curve and spotted a wire across the road,” said Harry Watts, a DR in Italy and northwestern Europe. “I just laid the bike all the way over and slipped under the wire.” He also reports near disasters from other booby traps, especially oil or horse dung spread on paved roads.

Deafened by their engines, DRs were easy prey for enemy strafing. Those who initially mistook sniper fire for wasps quickly learned the sound was a signal to gun it or scramble for cover.

“DRs in my section travelled anywhere from 4,000 to 7,000 miles per week, and not without severe casualties,” said Sergeant Morley Young in WWP. In six months he recorded six DRs killed, four seriously wounded and many injuries. “A total of 52 DRs passed through the section during this period, but we were rarely ever up to full strength of 35.”

The toll would have been much higher except for rigorous training in Canada and in Britain. They learned to ride safely over all types of terrain in all weather conditions. They were taught how to repair their bikes in the field, read maps and find their way in the dark, on unmarked roads, without headlights, dodging similarly blind vehicles.

Courses were so tough, recruits said, that it was battle—without enemy bullets. But that tough preparation “saved me from serious injuries on several occasions,” said Watts. Only a fraction of trainees went on to become DRs. “Of the 12 who started in our group, only four completed the course and two quit once we got overseas.”

Lapointe transferred to drive trucks for the Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers after a long, brutal ride across rugged country to deliver a merely personal message for his colonel. “My ass was so sore!” he said. But he hadn’t completely escaped from two-wheeled duty, as there were frequent DR shortages.

The job was hard and dangerous, but it also had its allure—and its perks. Because DRs were on call around the clock, they were exempt from mundane tasks, like guard duty, much to sergeant majors’ chagrin. They enjoyed a lot of freedom, often spending days away from chain of command. “It was also a neat way to pick up girls,” said RCCS Sergeant Jim Conway.

Using excuses like flat tires or broken chains, they could wangle extra free time to visit friends, explore the countryside or scrounge for food, equipment or supplies. In exchange for letting some American troops fire his tommy gun, Watts was rewarded with two cases of fruit cocktail for his unit mess.

“Independence as a DR was great,” said Aisbitt. “But it was a lonely job after June 6, 1944,” when solo assignments became the norm and DRs spent much of their time away from their units. It was not unusual for a DR to make a run and return to find his unit had upped sticks. “It was hide-and-seek time once more,” said Art Gaiger of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps.

DRs had to deliver their packets as fast as possible (there were no speed limits) over the shortest possible route. They had to be prepared to go without sleep, to sleep rough, to miss meals and to get themselves out of trouble. DRs routinely carried emergency food supplies, tool kits and spares for parts that frequently broke down. “I had a wrench and a screwdriver and that was about it,” recalled Watts. “If it needed more than that, then it was a wreck.”

Allen’s next trip behind enemy lines tested his luck. Ordered to take information to an American hospital, he came under enemy fire. At first, he thought a tire had blown, until he heard a second bang. “I rode the bike as far as I could, the tires all fell off eventually and I was riding on the rim and I was still going. I went for miles and miles until the spokes of my bike were coming through the rim. And on the cobblestone road, there were sparks flying… anybody could hear me…so I rode on the side of the curb on the grass.”

Headed for a bridge marked on the map, “I could see an 88—that’s German, it’s a fantastic gun they had.” Luckily, the bridge was being defended by a British airborne unit. He was stuck there a week. The only food was small fish they were able to catch in the river. Eventually they were relieved, and another dispatch rider came by and took his packet to its destination. Allen caught a transport back to his own unit.

“Anybody who said they weren’t scared, well, they weren’t telling the truth,” said army DR John Herbert Robotham. “I was scared all the time. You had to be scared. That’s why you kept alive…. You made sure you were doing the right thing.”

“In the mornings,” said Watts, “I would sit on my motorcycle and think of all the possible things that could happen to me that day, and think ‘what do I do if….” He got through the war having used just three motorcycles. “I was pretty good at fixing and repairing,” he said. “but when I got through with them, they were no good to anybody else. I wore them out.”

It is believed that DRs were in every major operation involving Canadian land forces (except for the 1943 operation on Kiska, an island in the Aleutians off Alaska). They served in North America, England, Europe, North Africa, Hong Kong and Siberia.

Sergeant D.G. Hutt of the RCCS was killed in 1940 in a motorcycle accident during the curtailed attempt by the British to create a diversion to draw some of the heat away from the French Army after Dunkirk.

In part of the same action, DR Bob Creighton of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment was taken prisoner when German troops seized the French hospital in which he was recovering from a motorcycle accident. He spent the duration as a prisoner of war, reported Farley Mowat in The Regiment.

On the ill-fated Dieppe Raid in August 1942, DRs were tasked with creating as much havoc ashore as possible, says WWP. A dozen motorcycles were outfitted with snorkels so they could go into action immediately, but none of the DRs made it off the beach.

DRs were often vital to operations. Within an hour of the decision to strengthen Canadian forces in the Mediterranean in the fall of 1943, DRs were speeding orders across Britain to more than 200 units, delivering plans and orders for mobilization of tens of thousands of troops to Italy and North Africa by January 1944. Later, in the slog to the Senio River in 1944, DRs delivered more than 28,000 packets.

Yet for all their heroism, for their great contribution to the war effort, little research has been done into the role of the dispatch rider.

“While a regiment’s history can be traced with relative ease,” says WWP, “dispatch riders and other military motorcyclists become lost in the paperwork they delivered with such dedication.”

Long after the war was over, Watts finally realized the role he had played in history. “The war was over and…you forgot about things,” he told Legion Magazine. “All of a sudden some little thing would pop up, maybe when talking to friends, and you’d say to yourself, ‘Oh, yeah. I was a part of that.’ At the time I had no idea. All I knew was I was busy riding the motorcycle.”

Follow

3.9K

Follow

3.9K