On this day, May 19, 1969. Motorcycle history.

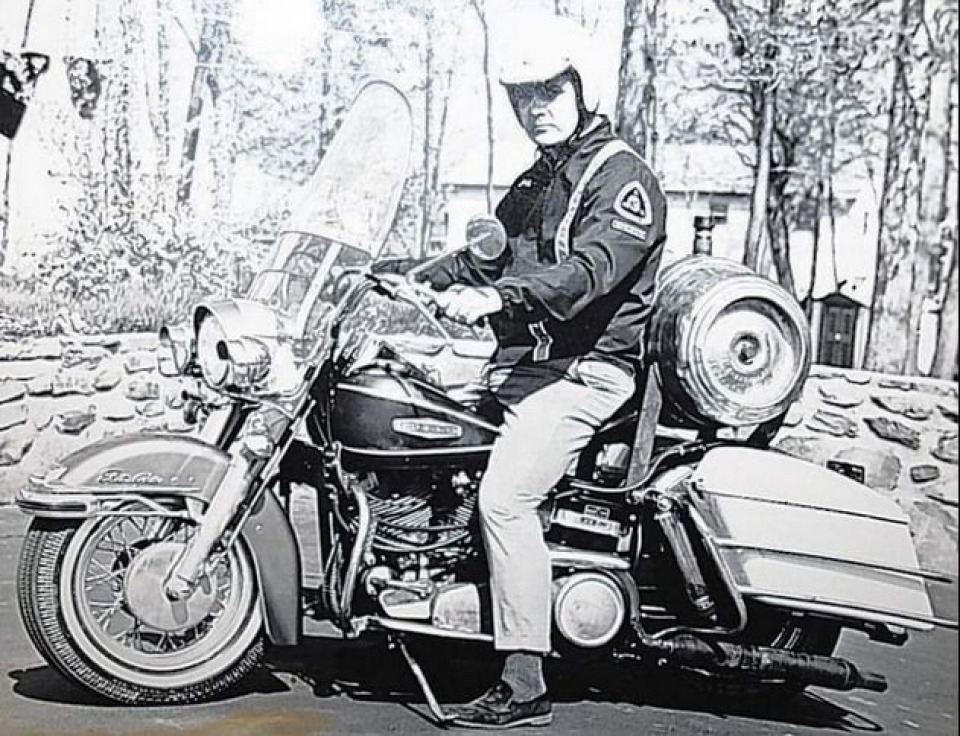

Today, May 19, 1969, New Windsor resident Leonard Baur set out to break the record of going solo cross-country (from New York City to Los Angeles) on a motorcycle. Even though he didn’t break the record (38 minutes over), it was an amazing test of endurance, stamina and riding experience.

It all started 43 years ago, when Leonard’s friend Sammy Armstrong, one of the first mechanics at Moroney’s Harley-Davidson, read about Tibor Sarossy in a magazine. The year before, Sarossy had set the cross-country record of 45 hours and 41 minutes riding a BMW model R69S.

The more they talked about the record that was set, the more Leonard believed he could do it, too. “Piece of cake,” Leonard said. “I didn’t realize what I was getting into, but this thing had a life of its own and it kept growing and growing and then it turned to some serious thought.”

Leonard started talking to different people about what he had to do to get his bike set up so he could do the trip. Lee Poland, a mechanic at Moroney’s Motorcycle Shop, which was on Route 9W at the time, gave Leonard a lot of advice.

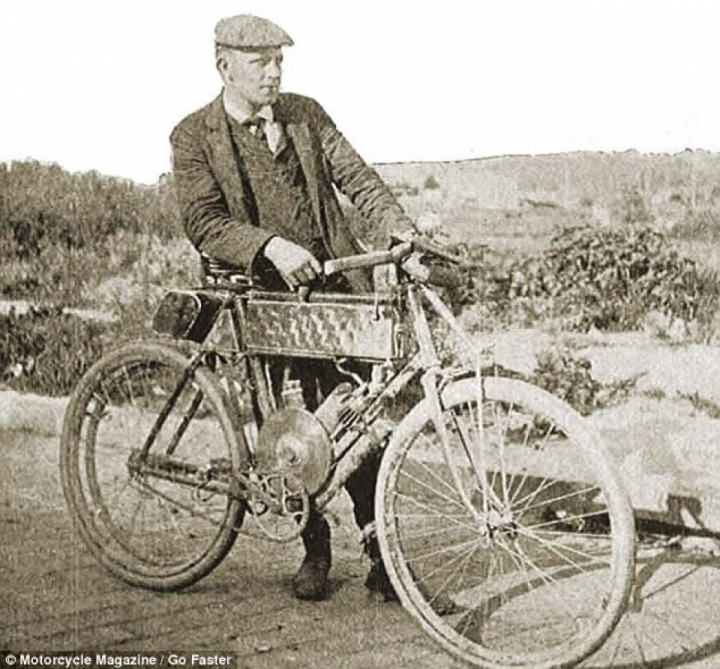

The most important aspect of setting up the bike for this long journey was how to carry extra gas. Tanks on a Harley only held five gallons. “I’m not sure who made the suggestion,” Leonard said, “but someone came up with the beer keg idea.”

Leonard acquired the keg from a local tavern, and took it to a local shop where aluminum and stainless steel could be welded. They cut the keg in half, put two baffles in it so that the gas would not slosh around and make the bike unbalanced and then welded it back together. Two pads were welded on it so that steel brackets could be applied so it could be bolted to the bike.

For the gas line feed, they ran a hose to the gas tank and put a valve on it. When Leonard hit the reserve and opened the petcock, gas would flow from the keg to the front gas tank.

Leonard then felt he really needed something to keep the oil cool. Temple Hill Garage gave him a power steering cooler to use on the bike as an oil cooler. They fitted the cooler to the bike and routed the oil through it. Mounted on the bike was a two-quart oil filter, and a hose was run down to where the chain and the rear sprocket came together. A valve allowed him to regulate the drip of the oil on the chain to keep it lubricated.

Jim Moroney gave Leonard a solo saddle seat, he gave the bike a good test run, put on new Goodyear tires and finally he was ready to go.

On May 12, 1969, Leonard set out on his journey, only to have it cut short. He was refused entry onto the New Jersey Turnpike because of high winds.

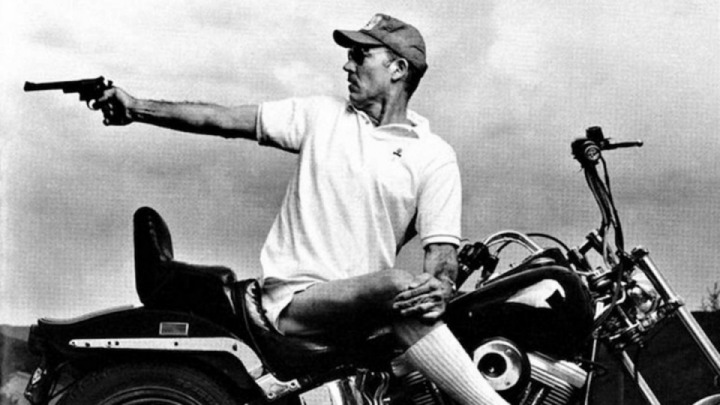

On his second attempt on May 19, Leonard made it to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, where he ran into traffic. “I gotta get around these cars,” Leonard said. “So I go through the opening. I get to the first car and there’s a Pennsylvania state trooper who pulls me over.”

The trooper wasn’t interested in hearing about what Leonard was trying to accomplish. He made Leonard wait until all the cars had passed before allowing him to enter the line of traffic again. He lost a lot of time.

Speaking of time, it seemed to drag for Leonard. If he had to make a bathroom stop, every four or five minutes ticked away. Leonard’s wife, Alice, packed him snacks that he ate while he rode. There was no GPS and no cellphones; it was just Leonard, the open road and the hum of his bike. He did have an Esso trip tick that outlined his route. But the ride also took a physical toll on him.

“The vibration on these bikes kills ya,” Leonard said. “After 10, 15 hours on a trip, your hands start to swell from gripping the throttle so tight. I was at a gas station, don’t know where I was, and the fella had a 35-gallon barrel of grease. I had a ring on and had to get it off ’cause my hand was swelling up, so I stuck my had in the grease to get it off. After that I walked around a little and ate some raisins before heading out again.”

“I think the adrenaline kept me awake,” Leonard said. “Actually, up until I got close to Los Angeles, I began to realize that I wasn’t going to break the record. Then, it was just exhausting, deflating and overwhelming.”

Disappointed, Leonard got back on his bike, found a freeway exit and fell asleep on his bike. A California state trooper woke him up and took him to a motel, where he slept for seven hours before calling his wife to tell her he had made it.

He told his wife he didn’t break the record, but he would make it up on the way back. But he was just too exhausted. When he got to Amarillo, Texas, he caught a plane home, leaving his bike in a motel garage. Three days later he went back to pick it up.

Follow

8.1K

Follow

8.1K