Motorcycle Parts Seller BikeBandit Has Stolen $646,000 of Customers' Money and Disappeared, Says Bankruptcy Trustee

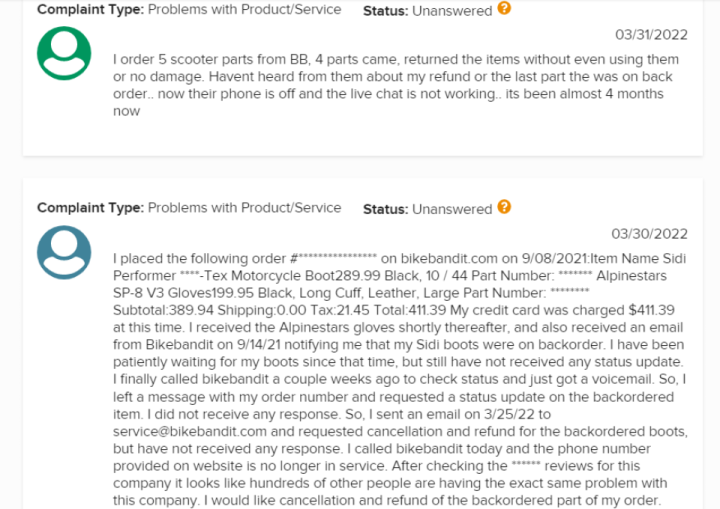

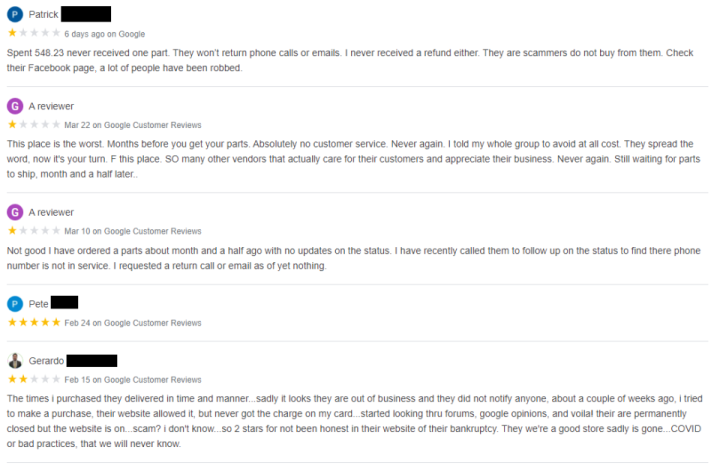

Motorcyclists around the country are confused and frustrated by BikeBandit, a well-known online seller of motorcycle parts and gear. Starting in late 2021, customers have been complaining that orders are never delivered, and refund requests are never answered. BikeBandit’s online customer service chat is broken. Its phone number is dead.

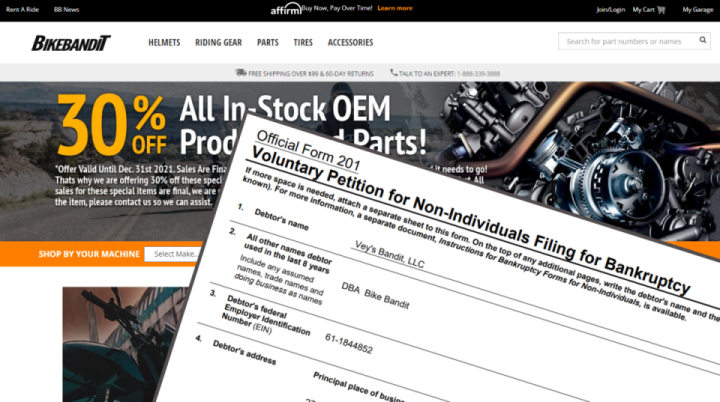

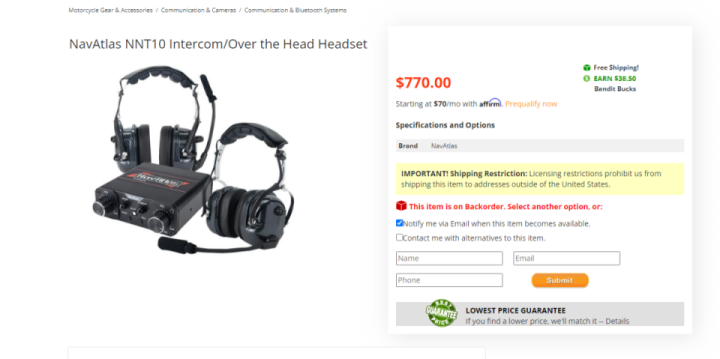

If you know where to search online, you’ll learn that BikeBandit quietly filed for bankruptcy in February 2022. But there’s no indication of that on the retailer’s website, where up until the middle of April 2022, you could fill a shopping cart, enter your payment info, and send your money to a defunct company that had no way to fulfill your order. Recently, one thing has changed: If you try to place an order today, you’ll be told the item is “on backorder.” But aside from that, the site is still running, even though the company is not.

Digging into the bankruptcy paperwork, it seems BikeBandit’s closure is just one piece in a complex web of apparent self-dealing, massive debts, and customer money disappearing.

If you’re a motorcyclist, chances are you’ve ordered something from BikeBandit. Any online search for bike parts, tires, or gear is likely to turn up a BikeBandit link, often with an enticingly low price. I’ve purchased motorcycle tires from the shop myself.

But things seemed to change in late 2021. According to complaints posted on the Better Business Bureau website as well as motorcycle forums, that’s when BikeBandit stopped shipping orders to customers.

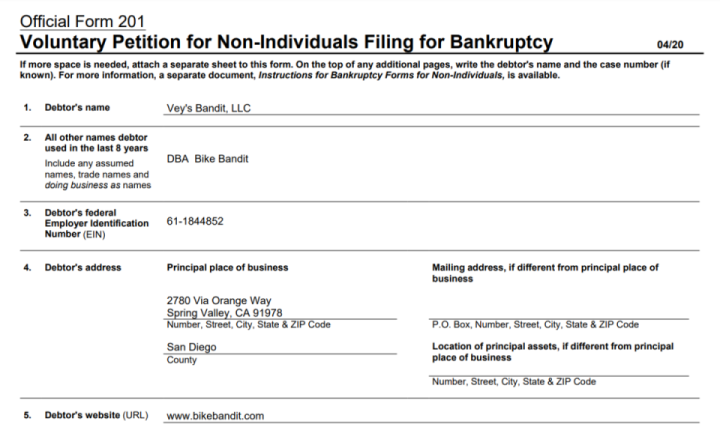

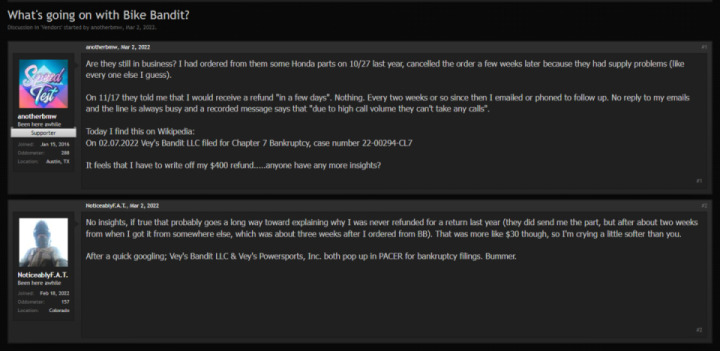

What happened? Bankruptcy papers filed in San Diego on February 7, 2022 tell part of the tale. That’s when Vey’s Bandit LLC — the parent company that operates BikeBandit — filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, relinquishing its online domain name and vacating its office and warehouse space. (You can view the complete bankruptcy filing here.)

I reviewed the legal filings with an experienced attorney whose specialties include bankruptcy law. The documents reveal that BikeBandit was just one part of a network of companies moving funds and assets back and forth — and BikeBandit’s bankruptcy seems to be an attempt to get rid of debts from elsewhere in that network.

BikeBandit was opened in 1999 by entrepreneur Ken Wahlster. Over time, it grew into a go-to online parts source for motorcyclists. In 2015, after a multi-stage acquisition, Affinity Development Group took over BikeBandit. The site claimed to have an annual revenue of $35 million at that time.

In 2017, BikeBandit was sold again, this time to the newly-created Vey’s Bandit LLC, a company wholly owned by Vey’s Powersports (a California motorcycle and ATV dealership), for an undisclosed sum. The person listed as 100-percent owner of Vey’s Powersports is Robert Rosenberg.

At the time of the bankruptcy filing, BikeBandit claimed to have $705,300 in assets — just $632 of which was in the company’s bank account — and over $19 million in liabilities. The company claimed to have $3.1 million worth of inventory, though elsewhere in the filing, the company anticipates the liquidation value of the inventory at a mere $400,000, a surprisingly low number even given the circumstances.

BikeBandit claims to have made $23 million in revenue in 2020, dropping to $7.7 million in 2021. With $19 million in debts, it seemed like this was a simple case of a company running out of money during bad economic times.

Then I started looking into how that $19 million of debt was calculated. At the time of filing, BikeBandit owed taxes in 36 states for sales completed in 2021. In some of those states, the company owed nearly $50,000 in taxes alone. Adding in debts owed to California’s Franchise Tax Board and the San Diego County Treasurer, BikeBandit owed $533,504 in unpaid taxes for 2021.

The majority of BikeBandit’s debts belong to a few heavy hitters. The shop owes $10 million to an individual, $2.9 million to a company called Vineyard Ranch LLC, and $1.9 million to Vey’s Powersports — BikeBandit’s own parent company. From there, the list of creditors is quite long and varied: unpaid utilities, plumbers, and garbage collection companies; money owed to motorcycle dealerships; and notably, a $590,000 debt to Google for online advertising. Four of the unpaid creditors have filed lawsuits against Vey’s Bandit LLC.

But let’s go back to the biggest creditors listed. Here’s the twist: On paper at least, BikeBandit’s biggest single debt is to its own CFO.

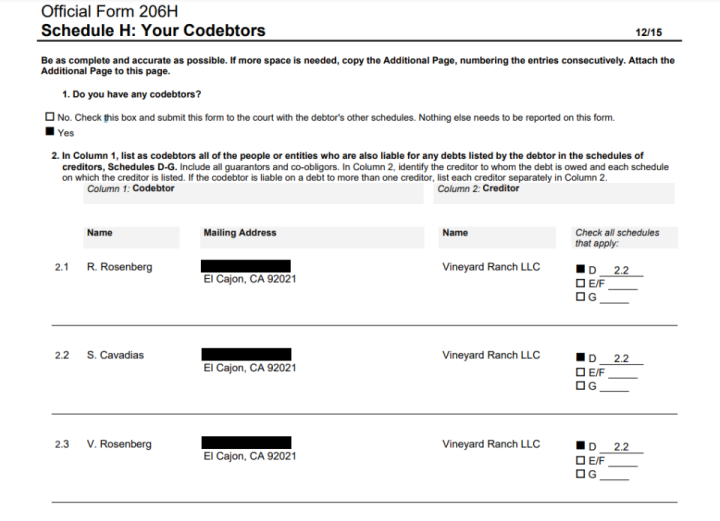

Three individuals are listed as codebtors on the amount Vey’s Bandit LLC paid to take over BikeBandit. According to bankruptcy paperwork, all three individuals operate out of an address belonging to Vey’s Powersports, the ATV dealership in El Cajon, California. In other words, these three individuals co-signed whatever debt BikeBandit owes Vineyard Ranch LLC. Redaction by me:

According to the bankruptcy filing, Robert Rosenberg is 100-percent owner of Vey’s Powersports (the dealership), which owns all of Vey’s Bandit (the parent company of BikeBandit); his spouse is Vicky Rosenberg. Cavadias is the CFO at Vey’s Powersports.

Per the bankruptcy filing, BikeBandit owes Robert and Vicky an unspecified amount of money. BikeBandit also owes some amount of money to a parts retailer called Adventure Twins LLC — 49 percent of which is owned by Vey’s Bandit LLC.

This would mean that BikeBandit essentially owes $11.9 million to itself, mostly for money loaned to the company by its owner and CFO. Put another way, the owner of all of these companies lists himself as a creditor to BikeBandit, and the money he says he’s owed is a big reason why BikeBandit folded.

What about Vineyard Ranch LLC? According to the original bankruptcy schedule, BikeBandit owes $2.9 million to this company.

Vineyard Ranch LLC is a real estate company owned by Gary Drean, who happens to be vice chairman of Affinity Development Group, the company that owned BikeBandit from 2015 to 2017. Drean was previously listed as a BikeBandit employee, and helped fund BikeBandit’s Baja 1000 sponsorship efforts through 2018. So in addition to BikeBandit owing itself a ton of money, the company owes a chunk of change to a former employee?

Not quite. On March 14, BikeBandit filed an amendment to its bankruptcy. The change? Vey’s Bandit LLC now says it owes $2.9 million to Affinity Development Group,& not Vineyard Ranch LLC as was previously stated. The amended document says the debt originated in 2017, when Vey’s Bandit borrowed money from Affinity Development Group to purchase BikeBandit& from Affinity Development Group. That debt, it seems, was never paid off.

Somehow, the more I researched BikeBandit’s bankruptcy, the more questions I had.

I’m not the only one with questions. On April 18, BikeBandit’s trustee — the independent, court-appointed person representing BikeBandit’s creditors in the bankruptcy proceedings — filed an application to the court to perform discovery on BikeBandit. In other words, the trustee is performing their own investigation into what BikeBandit claims on its bankruptcy. The attorney that worked with Jalopnik on this story notes that this is highly uncommon, and usually only happens when the trustee believes something in the filings doesn’t add up. The court has allowed the investigation to commence.

The answer to many of our questions comes from a freshly unsealed document from the trustee. (You can see the full document here.) In it, the trustee reveals that BikeBandit collected $646,000 in payments from customers on orders the company could never fulfill and failed to refund.

In court documents, the trustee makes it very clear that BikeBandit essentially stole this money from customers. In the following passage, “Debtor” refers to BikeBandit, and “consumer creditor” means any customer who paid for a BikeBandit order. Emphasis mine:

While additional discovery is needed, there is already ample evidence that the Debtor’s sworn bankruptcy papers filed in the case are factually untrue in material respects. Many creditors were omitted from the Debtor’s sworn bankruptcy papers.& For example, all of Debtor’s consumer creditors, many (possibly thousands) of whom deposited money with the Debtor that the Debtor later absconded with and others who purchased gift cards or earned “points” in a rewards program Debtor operated prepetition are altogether omitted from the Debtor’s sworn bankruptcy papers.

It remains unclear why the Debtor continued to operate its business well past the point of insolvency and, even worse, continued to accept online orders when it was apparent the Debtor would not be able to fulfill those orders. The Trustee is informed and believes that the Debtor contemplated filing bankruptcy as early as February 2021 and was unable to pay its debts as they came due no later than by that time. Despite these facts, the Debtor continued to accept online orders and charge consumers’ credit cards at least until weeks or days before the petition date, for orders that it was knowingly unable to fulfill from its available inventory. The Trustee also believes that the Debtor collected sales taxes on these phantom sales that were never returned to the consumer or remitted to the proper taxing authorities.

A footnote from that document makes it clear who got screwed in BikeBandit’s shady deals: “The Debtor’s sworn bankruptcy [documents] altogether ignore and fail to recognize debts of all kinds owed to consumer creditors, which involve many, many innocent individual consumer creditors.”

The attorney that worked with& Jalopnik on this story was able to answer a few additional questions based on what’s suggested in BikeBandit’s bankruptcy documents.

First: How does a company go under for owing money to its own proprietors? The attorney explained this situation is akin to a shop selling merchandise, then loaning that money back to itself. This turns revenue into debt, and debt can be a tax write-off.

The rest of the situation could be an example of a tactic often used by hedge funds and venture capital: Entrepreneurs will take the debt racked up by one business and dump it onto another, unrelated business. The second business then declares bankruptcy, which, if successful, will wipe out the debts, even though they weren’t accrued by that business to begin with. The business owner may even try to continue running the bankrupt business under a different parent company — conduct that BikeBandit’s trustee notes in court documents.

So given that BikeBandit (quietly) declared bankruptcy, does the continued operation of the website run afoul of the law? The attorney Jalopnik spoke with agreed with the trustee that wrongdoing may have occurred. Depending ››on what the trustee’s investigation reveals, BikeBandit’s continued operation could conceivably amount to bankruptcy fraud, a crime with consequences ranging from fines to up to five years in prison. The fact that BikeBandit collected $646,000 from consumers who never got their orders or refunds could lead to additional criminal or civil charges. Currently, no charges have been brought against BikeBandit or anyone involved in its operation, nor is Jalopnik aware of any other investigation into the business beyond the one being conducted by the bankruptcy trustee.

Information provided by the trustee answers a lot of questions, but more remain.

The trustee says that the money that was potentially stolen from customers went into the proprietor’s pockets, but why was it not used to pay down the company’s debts? Did BikeBandit’s operators intend to keep their online sales presence up and running, looking completely normal, even as the company was officially shuttered? Was there ever a plan to refund those customers their money?

In an effort to get these questions answered, I reached out to the bankruptcy court trustee assigned to this case. I also reached out to the trustee’s attorney as well as attorneys representing Rosenberg and Vey’s Bandit LLC. After multiple weeks, Jalopnik got no response from any parties involved.

There’s been one positive change in the story of BikeBandit. Currently, if you try to purchase anything from BikeBandit’s website, you get an error message that lists the item as “on backorder.” It’s no longer possible to pay money to the company for items you’ll never receive. But those items are not on backorder: They’re being liquidated as part of BikeBandit’s ongoing bankruptcy proceedings. The next hearing is scheduled for June.

Sourse: JALOPNIK

#Moto #Bike