The legend of the 80s moto guzzi tropicana.

A good part of the history of Moto Guzzi’s participations in the Dakar Rally, the toughest raid rally in the world, has first and last name: Claudio Torri.

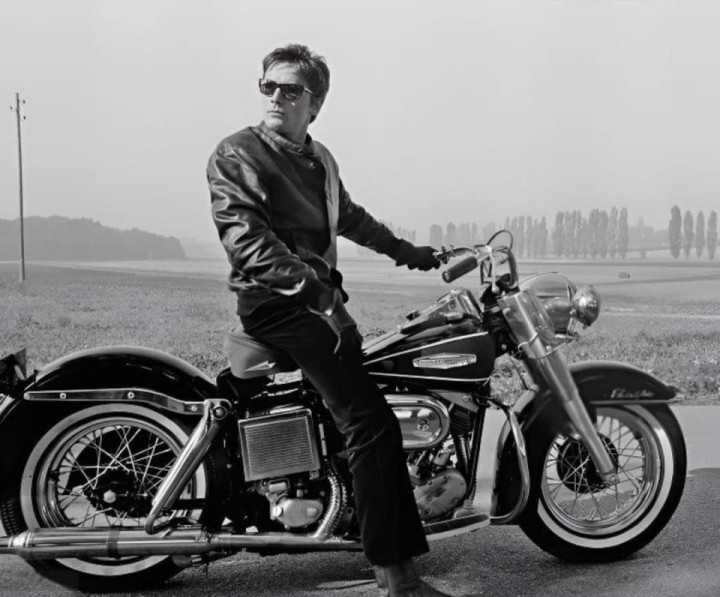

We have already had the pleasure to tell you about, with an exclusive interview, a few details of the four Dakar adventures with the Eagle built in Mandello of the likeable and headstrong architect from Bergamo (between 1985 and 1991), who has also recently tested a fiery V85 TT.

There are 4 Moto Guzzi prototypes that Claudio prepared for the “expeditions”, and that he loved in the same identical way, even if for different reasons, just as if they were his own children. Nevertheless, by investigating a bit it wasn’t hard to comprehend that there was, and still is, a special bond with one of these Eagles. The Tropicana perhaps was not the most victorious and top performing Guzzi, and neither was it the most technically refined, but all the same it was an innovative bike that became a witness and accomplice of a moment that changed Torri’s life during the 1988 Dakar Rally.

The Tropicana was also perfectly preserved and a few months ago we had the honour to bring it back to the historic factory in Mandello del Lario, right where it was assembled in record-breaking time 31 years earlier.

Claudio, let’s start from the beginning. When and how was the Tropicana created?

“My last Dakar Rally was the one in 1986 with the French team riding the prototype that originated from the Moto Guzzi V75. With this same bike, totally painted pink – I felt somewhat like an artist at that time [laughs] – I decided to not tackle the Dakar the next year, but instead to take part in the Wynn’s Safari in Australia in September. Then I left the bike with the Australian Moto Guzzi importer, so I found myself on foot just 3 months away from the January 1988 Dakar Rally, which I had naturally already decided to take part in as a private individual. Serafino and I in some way would have gotten a bike ready.”

Serafino was your mechanic, right?

“Serafino Valsecchi of the Moto Guzzi Testing Department. He was an engineer, a designer, a mechanic, an assistant in the field, he was a little bit all of my team [laughs]. Aside from 1986 with the French, I participated every time as a private individual and Serafino was the only one dedicated to following my follies, and then to coming with me to provide assistance. Luckily, I didn’t assemble the bike. I wasn’t able to even tighten a bolt. But I was one of the few authorised to drive into the factory with the passenger compartment full of bike parts and bottles of white wine. And so everyone knew me, and they fell in love with the project a bit at a time. We went back and forth from the Testing Department to the Engine Testing Room, which was at the end in front of the Wind Tunnel. I went to Todero and asked him for information. Leali designed the frame with me, then the tooling department made the parts for us. Guzzi’s mechanics were competent and my project took them somewhat away from the monotony of standard production.

I well remember the photographs that we took together after the Tropicana was finished. They were all pleased to have been able to lend a hand, some more and some less.”

How did you build it in just 3 months?

“To say the truth, I had already had the idea of building the first Moto Guzzi chain transmission conversion, which then I mounted on the Severe, but time was tight and we could count only on the mechanical parts that were on the shelves at Guzzi.

But I was sure of one thing. We would have built a one off motorcycle starting from zero, beginning from the frame and swingarm, which in the previous prototypes were taken from standard production and had always created problems. And so we started off from a beautiful brand-new frame in nickel-chromium-molybdenum steel connected to a box-type swingarm.

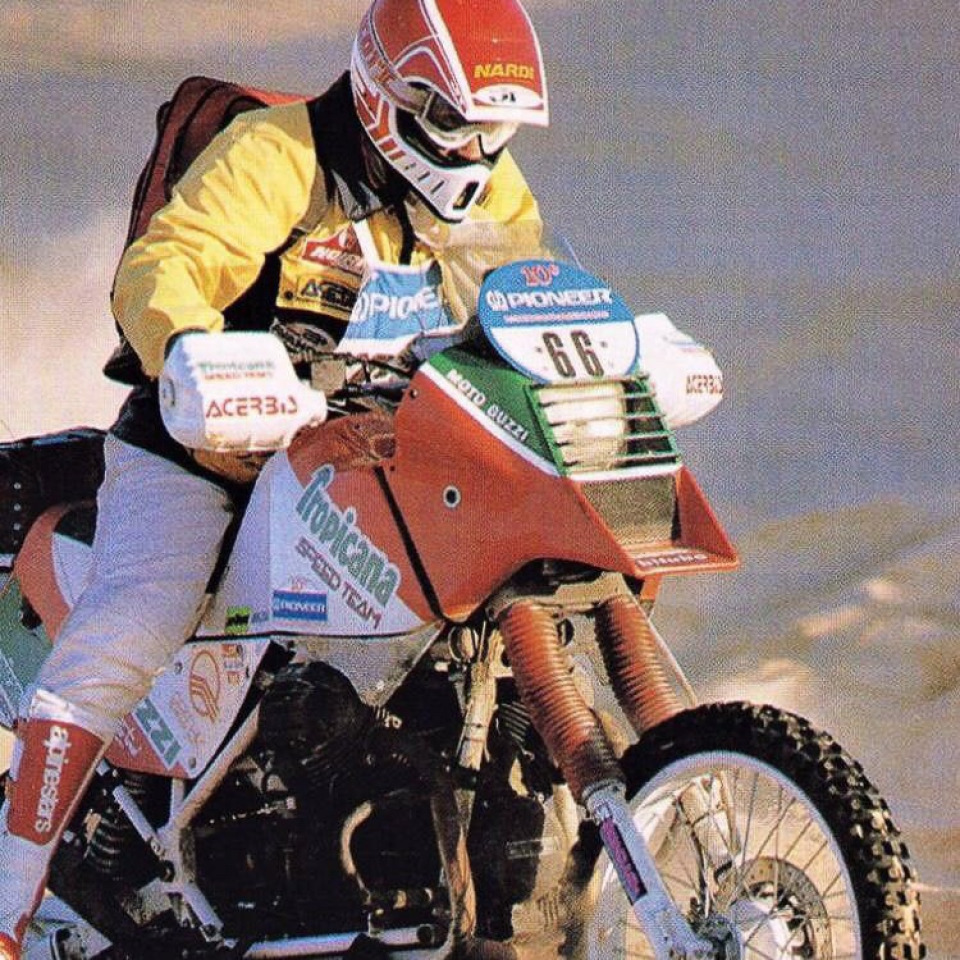

At first I would have liked to fit the small block 750 engine, but there was a lot less flexibility with parts, so we opted for the big block 2-valve 750 with round heads, coupled with a gearbox with straight teeth couplings and customized gear ratio: first and second rather long; third, fourth and fifth short, to get good traction on the sand.

Then there were the sintered clutch, 42 mm Marzocchi fork with 260 mm travel, Bitubo shock absorbers with 250 mm travel, Brembo single-disc brakes (260 mm fixed in the rear and 300 mm floating in front), an aluminium tank of about 44 litres, sealed Yuasa battery, Akront high-resistance rims and Michelin Desert tyres with mousses… those damned mousses!

As far as the racing equipment was concerned, the roadbook was already mechanical. The odometer was instead electrical (more accurate than the mechanical one), and then there was the compass that worked every now and then.

207 kg per 67 HP at the crank. I believe I still have the results of the engine tests somewhere. I almost forgot: a straight pipe exhaust, a real rumble of thunder!”

Where did the line and the name of the “Tropicana” come from?

“One day I was with my architect friend Ghilardini, who was the brain and hands behind all of the lines of my bikes. We took a tour through the Moto Guzzi Museum and we saw the 250 Bialbero, which has that characteristic beak, really unmistakable. And so we picked up that idea to both give continuity to the Eagle’s history and because of a technical issue: the beak allowed me to mount a low mudguard that better cooled the engine, and to conceal the oil radiator in a protected position excellent for cooling. It was a unique solution for 1987, and afterwards many started to adopt it.

Why “Tropicana”? It was thanks to the French importer Seudem, with whom I still had a great relationship and who found me this last-minute sponsor, the first and only one of my career as a rider, the renowned (at least back then) soft drink company. I liked the colours because they, in part, reminded me of the Italian flag, even if the red was replaced by orange.”

How did it go?

“We finished it a week before setting off for Paris, with Christmas and holidays in the middle, so as tradition would have it, I practically tried it out at the prologue. It was a heavy bike but with a good weight distribution and lots of torque to exploit in the sand, where in my opinion it did a very good job. It was somewhat long in wheelbase, so you lost some of the handling on the tighter stretches, but it was stable and quick in response on the fast stretches.”

We are talking about the 1988 Dakar Rally. How did it begin?

“As usual, the Dakar began with the prologue, which is a big event where all of the riders entertained the crowd, and we are talking about tens of thousands of people. However, let me say that that year it was something absurd. It was filthy. Videos are still to be found of the riders planted in the mud up to the half wheel, and obviously there is also one of my photos ingloriously stuck in the mud. To blame was the low mudguard that had compacted so much mud as to block the wheel in front. It was a ludicrous bother, but what fun it was!

Once the prologue ended, there was a lengthy transfer and then the ship for Algiers, and that was where the real Dakar Rally began, with a few early stages that were really gruelling. The truth is that the Dakar was so highly successful in those years that the organisation had to necessarily skim off a large number of teams in the early African stages, or else it wouldn’t have had the organisational means to lead everyone all the way to Dakar. It was tough, but we knew it. We knew that when the convoy reached the day of rest halfway through the race at least half of the team would be out of the running. Many of us simply didn’t care. I didn’t care. Those who had a chance to win could be counted on the fingers of one hand, and for the others the Dakar Rally was simply an epic adventure.

For the bikes, it was even worse than for cars and trucks. Just think: that year 183 bikers left and only 34 arrived at the finish line. A large part of the withdrawals was precisely in those infernal stages in Algeria. In fact, that was my destiny.”

What happened to you in the Algerian desert?

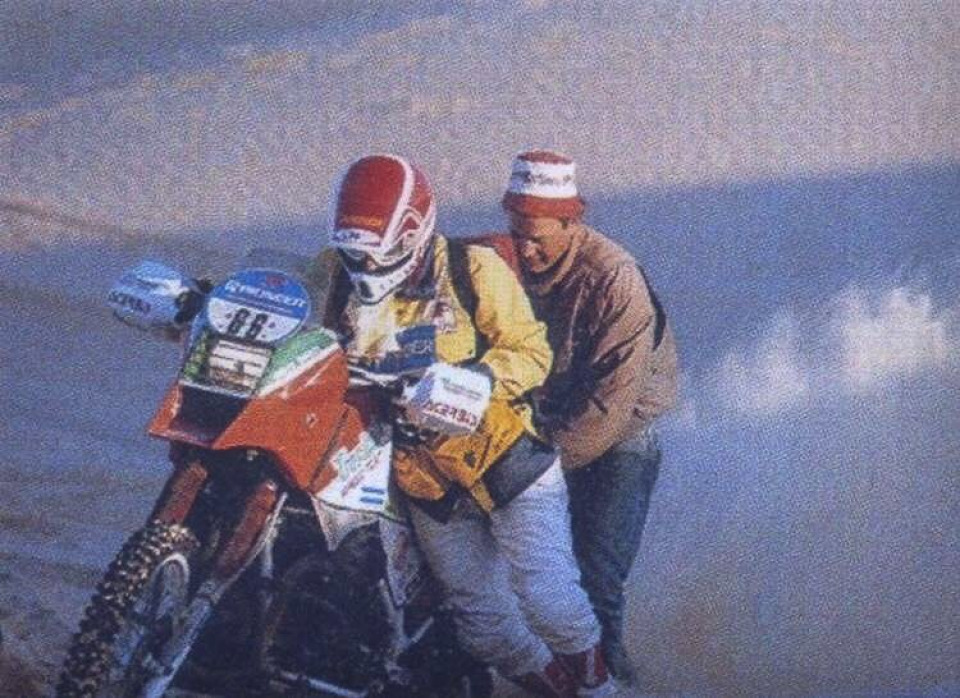

“We were about halfway across Algeria, at the third or fourth trial, in a stretch that seemed like an ocean of dunes having no logic. It was a nightmare for both getting your bearings and for moving in a straight line. You continued going up and down these small dunes that hindered visibility and forced you to make trajectories at an angle in order to not sink.

The trial wasn’t long, maybe 155 mi, and I was sure that I was on the right track, but that mousse that I had in the rear started to melt. It was something that happened with the early mousses back then, above all on the heavy bikes. It heated up to the point of melting and it became difficult to just disassemble the wheel without getting burned if you didn’t let it cool off. In any case, I was able to replace what remained of the mousse with an air chamber and to start off again, but just 31 mi later the tyre began to turn on the rim, becoming lacerated and preventing me from continuing.

That in itself wouldn’t have been such a big problem. I was on the official track so gradually everyone passed by, some of whom were ready to help. A few friends left me some food and water. They even offered me tyres and a replacement air chamber, but I had the problem of being the only one with a 17” rear rim, while almost all of the bikes had the 18” rim.

I have always been one who uses his wits, but there I simply could do nothing other than wait for the truck on which I had loaded the crate with my spare parts, including a complete rear wheel, to pass. But as cars and lorries passed by on the track, furrows formed, which the riders avoided, looking for parallel tracks to get round the obstacle. After a while, you couldn’t understand any longer what the real track was, and the landscape of small dunes hampered the view.

When the sun began to set, I understood that I would no longer be able to come across the truck with the spare parts, maybe it had taken a different route, maybe passing by at just a few dozen metres from me, and I simply couldn’t see it and stop it. I had to sleep there, in the desert.”

How did you feel there alone in the middle of the desert?

“I was neither afraid nor despondent, because that’s the way the desert is, you know it even before you leave. However, the first night was no easy task. The cold, the cold that I felt that night, I’ll always remember it. I did not have a sleeping bag because in these first short stretches you always relied on the assistance that followed you (yes, that’s right, the one that I was short of); I had only one of those aluminium thermal blankets, I had never grasped what they were used for. I covered it with sand so it wouldn’t blow away, and I slipped under it, to awake with my feet almost frozen.

You are at the Dakar, you are ready for unforeseen events and for reacting, but what you are not ready for is having nothing to do. Simply wait, because you know that you are in the right place and 124 mi away from the first town. But what I was less ready for of all was being alone with myself, forced to think about my “whims”, about my life, about the direction in which I was going.

The second night I kept my boots on. It went better with the cold, but up until noon I was no longer able to take them off because my feet had swollen. And yet, that morning I woke up different.

I had the bike on the kickstand, facing to the east. I stood on the foot pegs with my arms open wide to watch the sun rise. I felt the wind of the desert tell me that life was the most beautiful thing I had, and that I had to start over again. Those two nights saved me, forcing me with my back to the wall. That is how I became a man, hunkered down in the cold next to my Tropicana, and that is why a bond that goes beyond words has remained with her.

Two mechanics arrived on foot on the third day. It was the crew of the official Honda assistance truck that had sanded up off the track with its rear axle broken. The helicopter had caught sight of them and signalled to them to reach the official track to wait for the recovery lorry.

While we were waiting, I asked them where there lorry was, and if they had taken note of an azimuth with the compass to be able to find it in that sea of dunes all alike. They told me that they had forgotten and that now they had no idea where it was, certainly within a radius of a couple of mi, but impossible to see from a distance; it meant leaving it to the sand, but they had no desire to risk losing themselves again out there.

I, on the other hand, had by then made peace with the desert. I told them to wait there and that I would have gone to look for their lorry. Fortune had it that I found it. I noted an azimuth to mark its position and went back just in time to be picked up by the recovery truck.

That evening we found ourselves in a field together with the entire team that had remained blocked, and I realized what a massacre that stretch of desert was. It seemed like being in Rimini, there were 150 crews out of the approximately 600 that had set out on the trial, including Clay Regazzoni, the famous former F1 driver, who had broken his vehicle.”

How did you recover the Tropicana?

“This is the best part, because the bike was still there in the desert. From that mess of a field where we were there was no “legal” way to go recover it. The recovery vehicle, a gigantic lorry used for oil prospecting, was authorised to move to rescue only drivers and riders, but not vehicles, which would have been dozens and dozens.

But I have never left my Guzzi in the desert, and since I’m a man of the world, I was able to convince the Algerian driver to go back to recover the Tropicana, and while we were at it, to also tow the Honda assistance truck back onto the track. One thing has to be clarified: in the desert, the rule that what you find abandoned is yours applies… and I was the only one who knew where that truck was located.

With the Tropicana safe and sound, I “gave back” that lorry to the Honda mechanics. Let’s just say that without my help, and the spare engine that was on that truck, Edi Orioli would not have won the Dakar Rally that year.

I have never been a great rider, I was charismatic and everyone in that circle knew me, also for being a bit mad. After 4 days that no one knew where I had ended up, I was at the Niamey airport in Niger, where the Dakar convoy made a stop, dressed as a Tuareg. I gave both Serafino and everyone else a heart attack that time. In Italy, the newspapers bearing the headline “Claudio Torri missing in the desert” had already come out. But then what a party we had. We were really off our heads.

I went to get the Tropicana just one month later, in Hassi Messaoud where I had left it.

I can’t say that destiny exists, but at the psychological level I think that we all try to get ready for it. The destiny of the Tropicana was perhaps that of breaking down in the middle of the desert, and not because it was a bad bike, but because I could begin my resurrection.

You can appreciate a bike for its technical aspects, but only when you build a history together with it, a little personal legend, then you are really making a journey. It is somewhat like that with all Moto Guzzis. Each one is a symbol that tells stories and lets us live out new ones.”

Is there a question that you would have liked for a reporter to ask you in 1988 and instead never did?

“There is one. Never did a reporter ask me what I was doing at the Dakar, and like me, hundreds of other riders and drivers who were not racing to win.

If I did what I have done afterwards, including 20 years that I spent living in Africa and all the rest, it was due to these experiences in which I learned so much. And still I have never read an article talking about how the Dakar has been a school of life for many people. Otherwise, it would be impossible to explain how 150 bike riders left each year knowing that they would never reach the end.”

Will we see the Tropicana on the road?

“You can count on it! I have spent 25 years without talking about these stories, because I always thought that in order to live free and happy we should not live in the past. As Joyce wrote: “There is no past, no future; everything flows in an eternal present”.

But now that I’ve reached 68 years of age, I think I have earned the right to tell a few stories, including also the one about the Tropicana! After many years of silence, it’s time to start it up again to hear what she has to say, too!”

Follow

5.6K

Follow

5.6K