A Quick History Of The BMW R80 G/S

The adventure motorcycle genre is one of the most competitive sectors of the global motorcycle market, and it’s all thanks to the motorcycle you see here – the BMW R80 G/S.

Though of course there had been various other motorcycle developed for on and off road use, like the British scramblers that proved so popular in the mid-20th century, but the R80 G/S is widely considered to be the true origin of the adventure motorcycle species.

BMW R80 G/S – The Salvation of BMW Motorrad

Though it may be hard to imagine today, BMW had been a company in grave danger of going under during the 1950s and 1960s.

One of the things helping keep the company afloat was their motorcycle division, and their Italian-designed Isetta bubble car, a car so small that it prompted the Chairman of British Motor Corporation, Leonard Lord, to get his design team to create the iconic Mini so that people could have a “proper small car”.

As time went on however BMW made the bold move to create a new class of automobile which was appropriately called the “Neue Klasse”, and it would be these cars that would dramatically improve the company’s fortunes, with the BMW 2002 becoming the car that spearheaded that improvement.

With the changing of the market the BMW Motorrad motorcycle division continued to produce the same sort of conservative motorcycles that had served so well through the war years and that dedicated BMW aficionados loved: motorcycles that were built like a tank and which had the venerable horizontally opposed boxer twin cylinder engine whose original design BMW had quietly reverse engineered from a British Douglas motorcycle in the years after the First World War.

However, by the 1970’s, even as Bob Dylan continued to sing “The times they are a changing” the motorcycles from the Japan were literally conquering the world and rapidly driving the major British motorcycle makers out of business.

BMW’s motorcycle division was in no less danger of being beaten by the Japanese than the likes of Norton and BSA and as the 1970’s came to an end things were looking pretty bad: bad enough that in 1979 when Karl Heinz Gerlinger was made deputy director of BMW Motorrad he was given the brief to either make the motorcycle division profitable, or close it down.

BMW R75/5 And The ISDT Gold Medals

Almost as soon as production of the BMW R75/5 was underway in 1970 there were versions of the new model being modified for off-road racing. Legendary German enduro rider Herbert Schek would pilot his R75/5 to three championship wins in a row in the German off-road championship (over-500cc class).

Just for good measure he also won two gold medals in the ISDT (International Six Days Trial) a famously tough six day off-road motorcycle race that was famous for breaking both men and machines.

Some employees at BMW would later build themselves their own versions of the R75/5 ridden by Schek, and this would plant a seed that would result in 872cc prototypes that would become the race-only GS80 model, not to be mistaken with the later R80 G/S.

The GS80 would compete in the new-for-1978 over-750cc class in some forms of off-road motorcycle racing. Richard Schalber rode a GS80 to a win in the 1979 German off-road championship (over-750cc class). A year later in 1980 Werner Schütz repeated this feat while Rolf Witthoft won the European championship.

This set the stage for the arrival of the BMW R80 G/S that would go on to take multiple wins in the grueling Paris Dakar Rally, and establish the adventure motorcycle genre.

Karl Gerlinger And The Red Devil

Karl Gerlinger could see the writing on the wall: the British motorcycle makers had stubbornly stuck to making motorcycles that were very much built on an old tried and tested formula, and they were failing. BMW needed to pull a nice fluffy white rabbit out of a hat, they needed to do something that no-one would expect them to do, not even the Japanese.

Karl Gerlinger was not the only one at BMW Motorrad to have figured out the problem however, but a group of company engineers had been quietly doing some thinking and creating of their own and they didn’t just have ideas, they had a prototype built and in testing.

That prototype had been the brain-child of engineer Laszlo Peres who was an off-road motorcycle enthusiast, but more than that, he was a bit of a maven in that field and had been racing and tweaking BMW motorcycles for off-road competition for years.

When Peres and a group of engineers told Karl Gerlinger they had something to show him his interest was piqued and he went with them to be introduced to the “Red Devil.”

The “Red Devil” was essentially a boxer engine BMW motorcycle that had been modified for off-road and on-road use. It was sort of like a big enduro motorcycle with lights. The Japanese however pretty much dominated the enduro market with light single cylinder machines that were great off-road, but somewhat lacking on the highway. The “Red Devil” was heavier, but could do both.

This was a real adventure motorcycle, the sort of bike the intrepid early twentieth century “around the world” motorcycle pioneers would have loved. The Japanese were not making a motorcycle like this, in fact no-one was making a motorcycle quite like this, it essentially invented its own market segment, just as the successful Honda CB750 had done in creating the “superbike”. Karl Gerlinger decided to take the gamble and build the bike, hoping that this would prove to be the rabbit pulled out of the hat that would save the BMW motorcycle division.

Karl Gerlinger needed to get a new model into production quickly. He was under pressure from BMW senior management for him to do something about the motorcycle divisions waning fortunes, and he had little time in which to accomplish that. Could the “Red Devil” concept be turned into a game-changing motorcycle with minimal development time or cost? Could it be built predominantly using parts that were already in production for other BMW models?

Engineer Rudiger Gutsche was appointed as head of the development team for the new bike. Gutsche was an enduro rider and a self-motivated off-road motorcycle enthusiast who had a background in customizing BMW bikes.

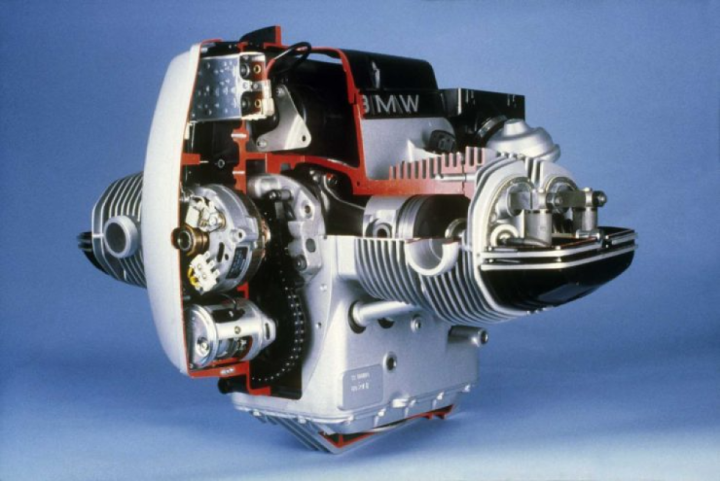

In looking at his options from the existing BMW model range Gutsche decided to use the R80 engine, which was having a lot of new development work done on it at the time, and the R65’s twin-loop steel frame.

The front forks came from the R100 but for the rear Gutsche decided it was time for something completely new and so he incorporated a Monolever design which combined the final drive and rear suspension into one simple unit.

Development work on the R80 engine included the changeover from steel lined cylinders to Nikasil (i.e. Galnikel coated aluminum) and the move to a combined flywheel and clutch assembly, these things resulting in the engine unit being made 20lb lighter.

Not only this but the engine received an electronic ignition system to improve reliability. For the new motorcycle’s off-road/on-road role the engine was also given a larger air-filter to better cope with dusty environments, and a two into one exhaust system which enabled mounting the exhaust up high and clear of the Monolever rear suspension.

A couple of pre-production prototypes were built and put through their paces down in South America, racking up a couple of thousand miles of testing. The bikes performed superbly and the decision was made to go ahead with production.&

The BMW R80 G/S Makes Her Debut

Before the BMW R80 G/S made her maiden debut at the Cologne Motorcycle Show in the autumn of 1980 a group of motorcycle journalists were invited to the famous Palace of the Popes, at the city of Avignon in the south of France, for a preview.

Many motorcycle journalists were perplexed with what this new bike was. It seemed to be an enduro motorcycle that was rather heavy, but that would be completely at home both negotiating rugged terrain or cruising up the autobahn. There were some who could see the potential, and many who doubted, until they had the opportunity to ride the bike and find out for themselves what the mavens at BMW had created, and what it could do.

The journalists grasped the concept, that this was an adventure motorcycle that would do the daily adventure through the city traffic, the weekend adventure out to a national park with a bit of off the beaten track thrown in, and the expedition from Cairo to the Cape.

What was even more important that what the journalists thought though was what the customers thought. Karl Gerlinger had been charged with significantly improving sales and it was customers with check books that would do that.

Happily at the Cologne Motorcycle Show the customers lined up in suitable numbers for the BMW team to realize they were on to a winner: they had indeed pulled a rabbit out of the hat. By the end of 1981 BMW had sold 6,631 R80 G/S motorcycles, which was about double the number they had hoped to sell. The R80 G/S had made a significant contribution to reversing BMW’s waning motorcycle sales, and on its own accounted for 20% of bikes sold.

BMW R80 G/S Specifications and Performance Characteristics

The “G/S” stood for Gelande/Strasse which translates into English as “off-road/on-road.” While the R80 G/S could not compete with a specialized off-road motorcycle in an off-road situation it could do what the off-road motorcycle could not do: it could comfortably cruise along the highway or autobahn for hours at normal highway speeds and also do some dirt and rough track negotiating as well.

This was flexibility that nothing else offered in quite the same way. On road and and dirt track testing the R80 G/S came across as a fully capable highway machine with the ability to go off road, but which did not have the rough going abilities of a dedicated off-road or even dual purpose motorcycle. Perhaps BMW should have called the bike the SG (Strasse/Gelande), as it was really more road bike than dirt bike.

On the road the acceleration was brisk in part thanks to the slightly lower 3.31:1 gearing of the transmission. It could get the jump on more powerful street motorcycles for the first hundred yards or so before the raw power and gearing of the purebred street bike would enable it to draw ahead. The R80 G/S tipped the scales around the 400lb mark and came with a 5.2 US gallon steel fuel tank to give it a range of around 250 miles.

The combined flywheel and diaphragm spring clutch system proved light and positive in use while the brakes were made for highway speed use, at the front being a 10.24″ (260mm) disc with Brembo caliper and semi-metal pads, and at the rear a 7.88″ (200mm) drum.

BMW understood the importance of getting the right tires on this machine and Metzler had come to the party with special tires not only off-road capable, but rated to 110mph highway speeds. Engine power was 50hp @ 6,500 rpm and torque 41 ft/lb @ 4,000rpm giving the R80 G/S a standing quarter mile time of 13.8 seconds and a top speed of 104mph. On early models an electric starter was optional, although all bikes for the US market were so equipped.

Front suspension of the R80 G/S was taken from the R100 and its telescopic hydraulic forks delivered 7.88″ (200mm) of travel. At the rear was the new Monolever swing arm system providing 6.6″ (170mm) travel. The BMW shaft drive produced the typical suspension rise and drop reaction on acceleration, something that would be addressed in the later models. The Monolever rear assembly enabled very easy removal of the rear wheel, requiring just three bolts to be removed.

When ridden on the street the R80 G/S felt lighter than its 400lb weight with the center of gravity feeling comfortingly low. The plentiful suspension travel still left the bike with crisp handling and the R80 G/S was a bike that could be thrown into corners with a degree of aplomb.

The small Bilstein rear shock absorber left room for improvement however and BMW found the need to offer a Koni optional unit with a remote reservoir for those who rode hard enough to discover the shortcomings of the original Bilstein unit. Off road, when the going got tough the long travel suspension would provide a good measure of comfort if the rider was going gently, as one tends to do on a long range adventure bike.

Pushed hard on rough surfaces however the softness of the suspension showed up as a disadvantage and could be hammered to the point of bottoming out. So this was not a bike for airborne excursions. The boxer engine’s cylinders hanging out from the side of the motorcycle also proved a tad awkward in the rough stuff, making it more difficult to put a foot down.

The fact that the cylinders were both equally out in the air flow was a preferable arrangement as far as cooling was concerned, which is the big consideration for an adventure or expedition motorcycle that will be required to run long and hard, often in extremely hot conditions.

The BMW R80 G/S in Competition

BMW had been active in motorcycle competition understanding the “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” principle that motorcycles that earn their street cred in competition automatically get a dose of buyer attractiveness at the same time.

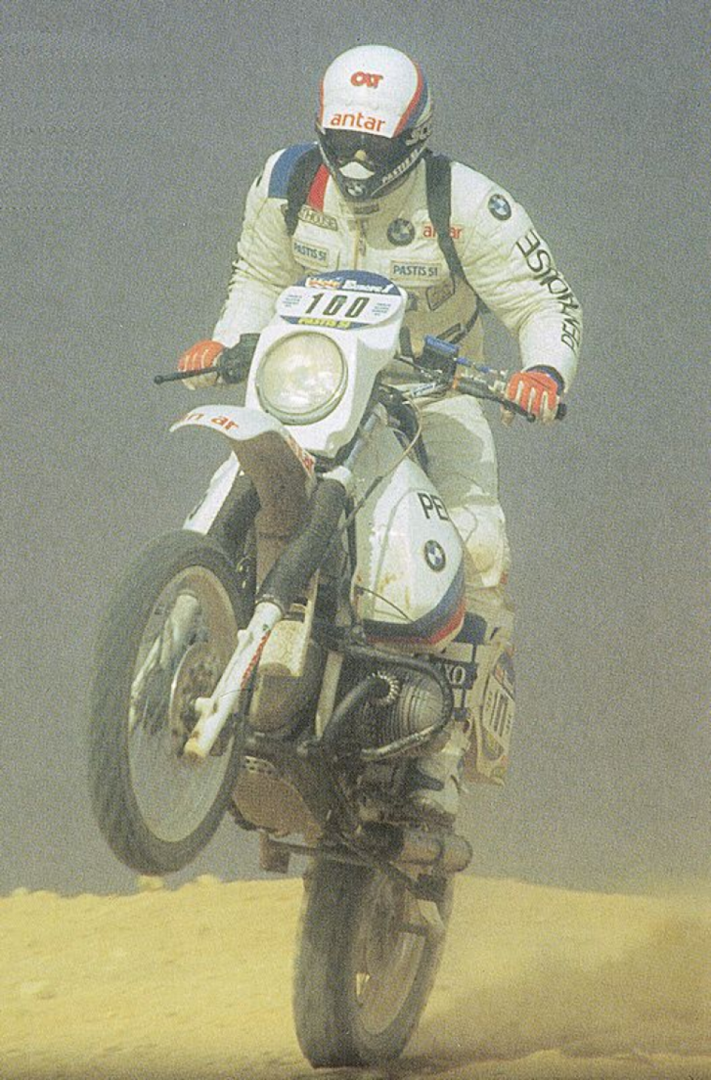

The BMW’s with their reputation for reliability were already a typical choice for motorcycle adventurers and the second Paris Dakar Rally in 1980 had seen Frenchman “Fenouil” (real name Jean-Claude Morellet) ride a BMW to a fifth place finish. With the R80 G/S aimed squarely at the motorcycle adventurer what better proof of the pudding could there be than to win the Paris Dakar?

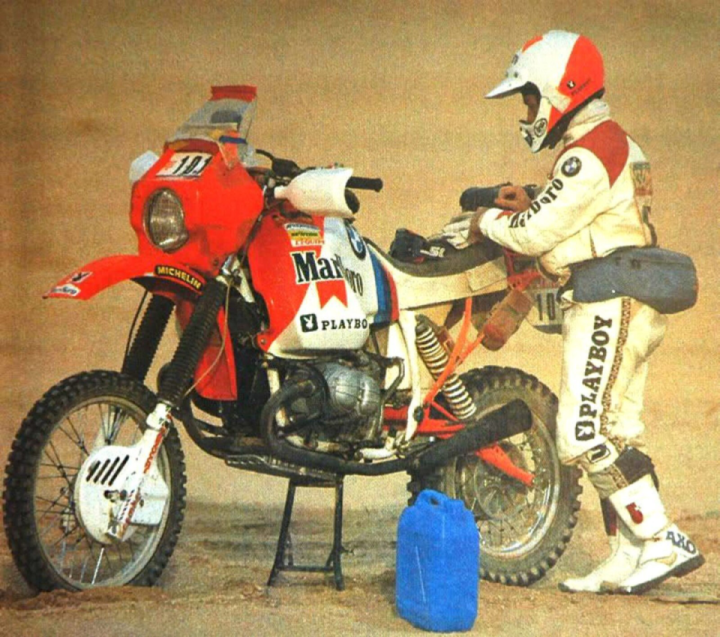

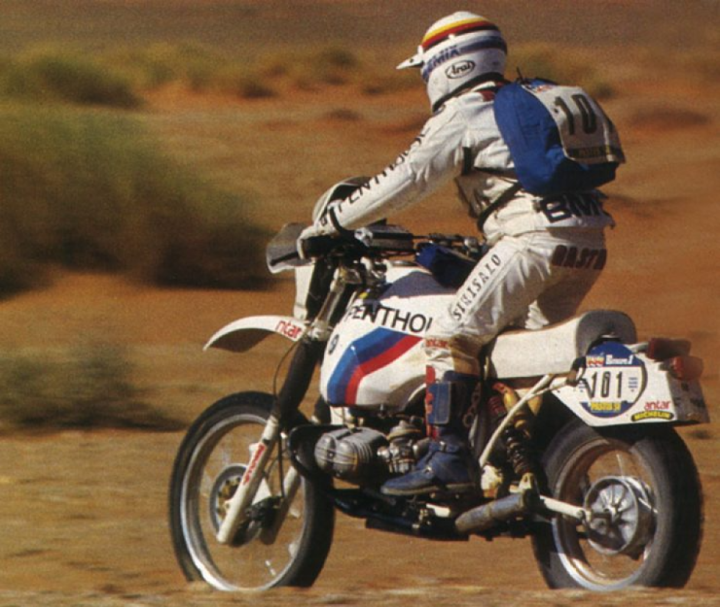

For 1981, the year of the R80 G/S public debut, BMW prepared works motorcycles for the Paris Dakar: the bikes being prepared by specialist HPN in Bavaria. The effort paid off and Hubert Auriol rode a works BMW to victory while Jean-Claude Morellet finished in fourth place and privateer German policeman Bernard Neimer came in seventh. It was enough for the motorcycle public to take notice and sales of the R80 G/S rose upwards in a most management satisfying way.

The Paris Dakar victories kept on coming with Hubert Auriol winning again in 1983 riding a BMW that was fitted with an engine modified to a 980cc capacity and 70hp power output by competition specialist Herbert Scheck. Not content with that Auriol went over to Mexico and won the 1,200 kilometer Baja California race as well.

For the 1984 Paris-Dakar things only got better with Belgian rider Gaston Rahier taking first place and Hubert Auriol in a respectable second. It was such a nice result that BMW decided to create a “Dakar” production model. Meanwhile Gaston Rahier went on to win in 1985 again. BMW followed that up with victories in the 1985 and 1986 Baja California shared between Gaston Rahier and Eddy Hau.

By 1987 more than 21,000 BMW R80 G/S had been sold and the possibility that BMW’s motorcycle division might be closed down was reduced to a bad memory, now past.

Developments and Sibling Models: The BMW R80 G/S Becomes the R80 GS

The first of the special models was the “Dakar” of 1984. This bike was fitted with protective bars, a single seat, luggage rack, Michelin rough tread tires, and boasted a whopping 8.45 US gallon (32 liter) fuel tank making it a bike capable of butt numbing distances between trips to the gas station.

Not only was this made as a regular production model but a conversion kit was also made for those wishing to re-model their stock R80 G/S into a Dakar bike. The model was popular with about 3,000 being sold.

In 1987 BMW set about making improvements to the R80 G/S which resulted in them offering both an upgraded and renamed R80 GS and an R100 GS fitted with a 980cc engine producing 60hp @6,500rpm. Both these models were made with a significantly improved rear suspension. The Monolever rear suspension had been prone to the characteristic shaft drive induced rise and fall, which riders could adapt to, but would prefer not to have to deal with.

Paradoxically BMW had developed a solution to this effect way back in 1955 when engineer Alex von Falkenhausen had patented technology of a rear swing arm system using parallel arms. The system had been used on racing machines, but not on production bikes, most likely because the “shaft effect” did not really manifest itself as a problem unless under power on a rough surface.

The R80 GS and R100 GS were both being used with power on rough surfaces and so the incorporation of this system made sense. The new rear suspension was single sided, called the Paralever, and it was welcomed by customers as a great improvement.

The improvements did not stop at the rear however. As noted earlier the front forks of the original R80 G/S could be made to bottom out, especially if the bike was jumped. To eliminate this problem BMW not only strengthened the front forks but also introduced the new travel dependent damping technology.

This worked by having a conventional left side fork connected to the right fork, which was fitted with a bushing that responded to violent compression of the left fork by stiffening the system to resist bottoming out.

Complimenting this new technology the front axle was made as a 1″ (25mm) diameter hollow unit both stiffening the assembly and keeping it light while reducing fork contortion. The new wheels were the icing on the cake: these cross-spoke wheels provided a flat spoke-angle greatly improving wheel stiffness and resistance to impacts: they also allowed the use of tubeless tires.

The new models also boasted 26 liter fuel tanks in place of the previous 19.5 liters: the Dakar retaining its long range 32 liter tank. Other improvements were the use of wind-tunnel developed front mudguards to reduce front-end sway at high speeds, larger seat, larger battery, and an alloy plate underneath providing protection for the sump and exhaust manifold.

Not only did the R80 GS acquire a larger sibling, it also got a smaller one. Made for new riders and those who might feel a bit intimidated by an 800cc or bigger engined, 400lb motorcycle, BMW made the smaller capacity R65 GS.

With an engine that was a couple of inches smaller in width than the R80 GS and producing a modest 27hp the R65 GS was still capable of a “wind in the hair” 91mph (146km/hr) top speed, which is a not insignificant speed for a new rider, and for those of us who love life generally and have no real desire to do the ton. The R65 GS sold in smaller numbers than its bigger siblings but with its nice handling and adequate speed was and still is a great motorcycle.

The R80 GS was pushed into the background to an extent by the new R100 GS Paris-Dakar which became a machine of choice for serious adventurers and those interested in competition. By late 1986 BMW were winding down their involvement in the Paris Dakar race and leaving it to privateers.

Eddy Hau won the Marathon Class in the 1988 Paris Dakar while lady rider and BMW engineer Jutta Kleinschmidt used a near stock standard R100 GS to gain a fifth place in the Paris to Cape Town Rally, a journey of 12,700 kilometers, which is a heck of a long way on a motorcycle.

Conclusion: All’s Well That Ends Well

The R80 GS continued to enjoy progressive upgrades over the decade from 1986 on up until the final 1996 two valve model, the R80 GS “Basic”.

This was the model that heralded the graceful denouement of the motorcycle that had, arguably, saved the BMW Motorcycle Division’s bacon, and had done it by creating a new type of motorcycle for the ever vigilant Japanese to try to duplicate. The final production run of the R80 GS would be 3,003 motorcycles and it would be phased out of production in 1997.

The R80 G/S was a high stakes gamble on the part of BMW Motorrad, it was a gamble on which their survival depended: it was rather like the instruction that Yoda gives to Luke Skywalker in “The Return of the Jedi” when he says “do or do not, there is no try”.

Despite the BMW R80 G/S’s initial shortcomings it was a motorcycle that hit just the right spot in the imaginations of adventure motorcycle riders who embraced the bike whether or not the motoring press were unanimously praising it.

Today it is a great bike to own and enjoy, and a bike that has earned a place in any collection of significant BMW motorcycles: without it it is quite probable that BMW Motorrad would no longer be with us.

Credit: silodrome

#BMW #R80 #GS #Moto #Adventure