Jeff Cole’s a motorcycle racing pioneer

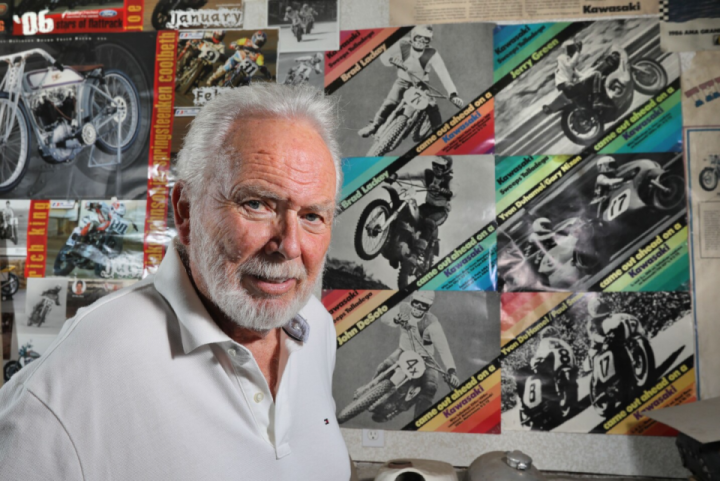

Jeff Cole’s design work on racing motorcycles over the past half-century earned him a spot in the Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

Virtually every racing motorcycle on the road today bears Cole’s fingerprints. Through his company C&J Racing Frames, Cole made motorcycles faster, nimbler and safer by refining the shape, style and weight distribution of their steel frames.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, motorcycles with C&J frames won 20 American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) Grand Championships for riders including Ricky Graham, Scott Parker, Kenny Roberts and Chris Carr. Even today, companies like Harley-Davidson and Indian Motorcycle fly their engineers to Fallbrook to consult with Cole on frame designs.

Before Cole’s AMA Hall of Fame induction last fall, his role in history was summed up by Steve Johann, who produces and co-hosts the cycling industry’s “Hog Radio Show.”

“Jeff’s a brilliant fabricator,” Johann said. “He could translate rider feedback, whether highly technical or casual commentary, into geometric expressions that helped racers win. In many ways, his revolutionary frame designs changed the racing landscape by accomplishing what was previously thought impossible.”

Not bad for a college dropout with no training in engineering, design or physics. Cole was just born with a flair for tinkering, a skill for turning ideas into designs and a passion for racing.

Cole grew up in Santa Ana, where his parents owned a ranch with more than 500,000 chickens. As a boy, he was always building wheeled contraptions to carry heavy loads around the ranch.

By the time he finished high school in 1960, he’d used his savings to buy a 1959 Corvette and 1957 Chevy. And when things went wrong under the hoods of these cars, Cole learned how to fix them from his cousin Don Edmunds.

In 1957, Edmunds won the Indianapolis Speedway’s “Rookie of the Year” award, but retired from racing after a dangerous crash in 1958. After that, he switched to building race cars at a garage in Anaheim.

After high school, Cole studied business at Menlo College but he wasn’t inspired, so he quit and came home to look for work. In the summer of 1962, Edmunds hired Cole to join his racing team’s pit crew in Indianapolis.

Cole’s first job was scribbling chalkboard messages for Indy drivers as they sped by. Over the next eight years, he worked his way up to shop manager, helping Edmunds build Indy cars, sprint cars and midget racers.

“I fell in love with oval-track racing,” Cole said. “My cousin put me to work and I picked it up like I had been doing it my whole life.”

By 1970, Cole was married — he and his wife, Jill, will celebrate their 50th anniversary this summer — and eager to start his own fabrication business. But out of respect for his cousin, who’d taught him everything, he wanted to go in a different direction.

“I didn’t want to compete with him. I wasn’t sure what to do until someone came to me and said ‘everyone’s working on cars but nobody does motorcycles.’ So that’s what I decided I’d do,” Cole said.

Cole didn’t have any experience in the field. His mother had forbidden him from riding motorcycles as a boy, so his main exposure was as a teen, attending the Friday night motorcycle races at Gardena’s Ascot Raceway. But he knew the principles for racing design were the same, regardless of whether the vehicle had two or four wheels.

“The whole motorcycle world is all about geometry — the wheel base, the weight on the wheels, the ground clearance,” he said. “I learned how to do it by talking and listening to riders who told us what they liked and what they didn’t. Then we’d go back and tweak things here and there. It was a seat-of-the-pants style of working.”

In 1970, he co-founded C&J Precision Products with Steve Jentages, a former roommate and high school classmate who’d also grown up building cars and was an expert welder and fabricator.

They opened their first shop next door to the newly established Kawasaki racing motorcycle R&D lab. Before long, Kawasaki’s engineers asked C&J to convert one of their quick-fill auto gas tanks for use on a motorcycle.

Pleased with the result, Kawasaki then asked them to build a motorcycle frame (or chassis) for one of their sponsored racers, Brad Lackey. Using that frame, Lackey won the 1972 AMA Grand Prix. Then he took the bike to Europe, where he became the first American World Champion Motocross rider.

After that, motorcycle manufacturers were beating a path to their door. Design directors at companies like Suzuki figured out that Cole and Jentages could turn around a new frame design in a few weeks, a fraction of the time it would take at the corporate level.

Their most high-profile client in those years was Evel Knievel, the cycling daredevil who hired them build a rocket around a motorcycle frame for his failed attempt to soar over Idaho’s Snake River Canyon in 1974.

One of their top achievements was the creation of the monoshock, a single shock absorber that replaced the standard twin shocks in the early 1970s. That’s now standard equipment on many racing motorcycles.

But by 1976, Cole wanted out. He and Jill had two young children and he wanted them to have the same experience he did growing up in the country.

Forty-one years ago, the Coles moved to a five-acre ranch in Fallbrook. After an unsuccessful effort to run the newly named C&J Racing Frames long-distance with Jentages, they decided to dissolve their partnership.

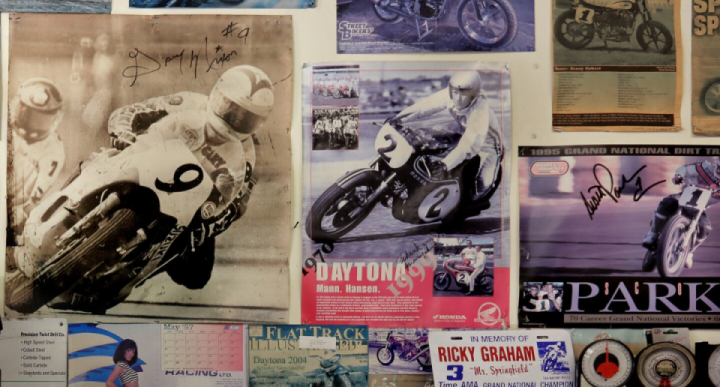

Cole carried on the business for the next 28 years until he sold it in 2004. Among his top achievements over the years were two cycle frames he built for Honda in the early 1980s. The twin-engine RS750 is so beloved by collectors, there’s now a coffee table picture book about it in the production stage. The Honda flat-tracker NS750 is also highly prized for its frame and engines.

C&J’s reputation endures in the dirt-racing world. A Facebook group page titled C&J Framed Motorcyces has nearly 1,000 members from as far away as Australia and New Zealand.

These days, Cole is mostly retired. He and his wife, who taught for 30 years in the Fallbrook school district, spend up to four months a year at their beachfront home in Baja’s Buena Vista. He also enjoys marlin fishing and crewing on racing sailboats, hobbies he took up decades ago.

The metal fabricating machines in the garage at their Fallbrook ranch are now mostly idle, but every inch of the shop’s walls are covered with autographed posters from cyclists who’ve won races on C&J frames.

While he’s honored to have been inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame, Cole said what means most to him are the opinions of those riders and the engineers he worked so closely with to bring their visions to life.

At the ceremony October 2016, the CEO of Indian Motorcycles asked Cole to autograph the prototype that he’d helped develop in that consultation with Indian engineers at his home two years ago.

“That meant a lot to me, even more than the Hall of Fame thing did,” Cole said. “I had a hand in that Indian and it’s now winning every race out there.”

Credit: sandiegouniontribune

#Moto #Bike #Technologies